A little-known element is offering new insights into the transatlantic slave trade. Researchers have created a map of strontium, a naturally occurring element, across sub-Saharan Africa. By comparing these strontium levels with those found in human remains, scientists can more accurately determine the geographic origins of individuals sold into slavery, as reported in Nature Communications on December 30.

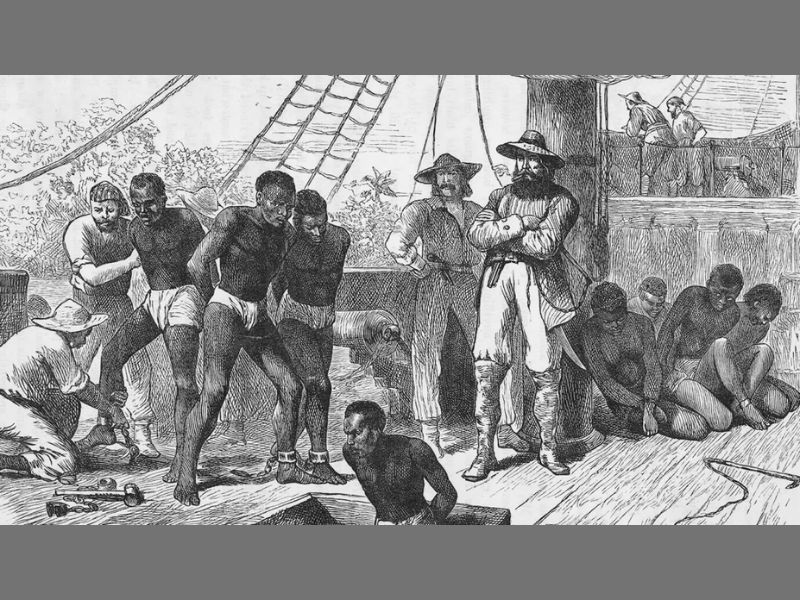

Between the 15th and 19th centuries, over 12 million Africans were enslaved and transported to the Americas and Europe. Major port cities like Lagos, Nigeria, and Luanda, Angola, were common departure points, but the specific origins of most enslaved people—where they were born and raised—often remain unknown. While genetic evidence can identify ancestry, it does not reveal the exact locations where people grew up.

Strontium’s Role in Tracing Origins

This is where strontium plays a key role. The geological makeup of a region determines its unique ratio of strontium isotopes—variants of the element with different atomic weights. Strontium is easily absorbed by living organisms and is present throughout the human body. “It’s in everything and everyone,” says Vicky Oelze, a biological anthropologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

By analyzing strontium isotope ratios in plant or animal remains, researchers can trace an organism’s geographic origins. “Each organism retains the signature of its evolutionary environment,” explains Lassané Toubga, an archaeologist at Université Joseph Ki-Zerbo in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.

Creating strontium isotope maps, however, requires extensive sampling of soil, plants, and animal remains. Oelze, Toubga, and their team spent over a decade collecting nearly 900 environmental samples from 24 African countries, supplementing their data with existing studies to develop a comprehensive strontium map of sub-Saharan Africa.

“This map reflects the collaborative efforts of more than 100 experts from various fields, including archaeology, botany, zoology, and ecology,” notes study coauthor Xueye Wang, an archaeologist at Sichuan University in Chengdu, China.

Mapping Sub-Saharan Africa to Uncover Historical Insights

The researchers focused on sub-Saharan Africa due to its significance in areas like archaeology and conservation, where strontium data can be particularly valuable. They also believed that such a map could uncover new insights into the transatlantic slave trade, as most enslaved individuals originated from this region.

To explore this, the team analyzed published strontium isotope ratios from the dental remains of 10 enslaved individuals buried in Charleston, S.C., and Rio de Janeiro.

Comparing these data with their strontium map revealed details that genetic analyses alone couldn’t provide. For example, two men buried in Charleston, Daba and Ganda, were previously identified as having general West African ancestry. Strontium analysis, however, narrowed their likely origins to southwestern Ivory Coast, southern Ghana, or eastern Guinea.

Pinpointing an individual’s geographic roots is crucial for understanding their identity, notes Toubga. “Determining the origins of enslaved people helps identify the cultural or political groups they belonged to.”

While more environmental samples would improve the map’s spatial resolution, Murilo Bastos, a bioarchaeologist at the National Museum of Brazil not involved in the study, praises the work. “It’s a major accomplishment,” he says.

Read the original article on: Science News

Read more: Tiny-Brained Ancestor May be History’s First Gravedigger and Artist