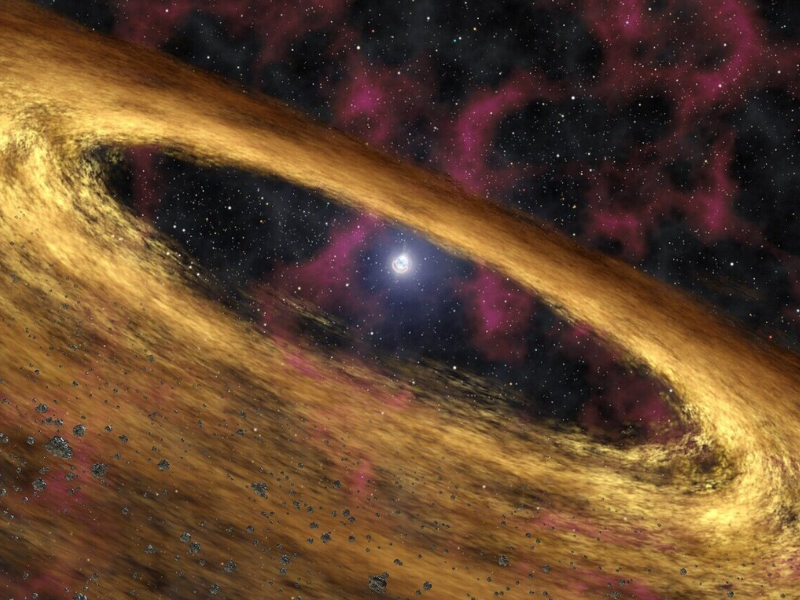

The flashing of a nearby star has attracted MIT astronomers to a new and mysterious system 3,000 light-years from Earth. The stellar oddity seems to be a new “black widow binary,” a rapidly rotating neutron star, or pulsar, circling and slowly consuming a smaller companion star, as its arachnid name does to its companion.

Astronomers know about two dozen black widow binaries in the Milky Way. This newest candidate, called ZTF J1406 +1222, has the shortest orbital period yet recognized, with the pulsar and companion stars circling each other every 62 minutes. The system is unique since it seems to host a 3rd, far-flung star that orbits around the two internal stars every 10,000 years.

The existence of this probable triple black widow pulsar system prompts inquiries regarding how such a complex structure could have originated. Based on their observations, the MIT team proposes a possible origin story: Similar to most black widow binaries, this triple system probably formed within a dense grouping of aging stars known as a globular cluster. This particular cluster may have gradually drifted towards the center of the Milky Way, where the gravitational forces generated by the central black hole were strong enough to break the cluster apart, but not enough to disrupt the triple black widow pulsar system.

Birth of a star system

According to Kevin Burdge, a Pappalardo Postdoctoral Fellow in MIT’s Department of Physics, the birth scenario of this system is intricate. He suggests that this particular system may have been present in the Milky Way for a longer duration than the sun’s existence.

Burdge is the author of a study today in Nature that details the group’s discovery. The researchers used a new method to detect the triple system. While most black widow binaries are located through the gamma and X-ray radiation released by the central pulsar, the team utilized visible light, particularly the flashing from the binary’s mate star, to detect ZTF J1406 +1222.

Burdge says: “This system is exceptional as far as black widows go since we found it with visible light, and due to its wide companion, and the simple fact it came from the galactic center.” “There is still a lot we do not understand about it. However, we have a new way of looking for these systems in the sky.”

The research study’s co-authors are collaborators from several institutions, including the University of Warwick, Caltech, Maryland, Washington, and McGill University.

Night and day

Pulsars power black widow binaries, quickly spinning neutron stars that are the collapsed cores of giant stars. Pulsars have a dizzying rotational period, rotating every few milliseconds and releasing flashes of high-energy gamma and X-rays in the process.

Usually, pulsars spin down and die fast as they burn a significant quantity of power. However, periodically, a passing star can provide a pulsar new life. As a star nears, the pulsar’s gravity removes the star’s material, which provides new power to spin the pulsar back up. The “recycled” pulsar subsequently starts reradiating energy that further strips the star and destroys it.

“Black widows are the system’s name because the pulsar kind of consumes the thing that recycled it, similarly as the spider consumes its companion,” Burdge says.

To this date, every black widow binary has been identified through gamma and X-ray flashes from the pulsar. Initially, Burdge encountered ZTF J1406 +1222 through the optical flashing of the companion star.

The companion star’s dayside: the side perpetually encountering the pulsar can be hotter than its night side due to the constant high-energy radiation it obtains from the pulsar.

“I presumed, instead of looking for the pulsar, try searching for the star which is cooking,” Burdge explains.

He reasoned that if astronomers observed a star whose illumination was transforming periodically by a significant amount, it would be a powerful signal that it remained in a binary with a pulsar.

Star movement

To test this theory, Burdge and his partners browsed optical data taken by the Zwicky Transient Facility, an observatory located in California that takes wide-field images of the night sky. The team studied the star’s brightness to see whether any were changing drastically by a factor of 10 or more, on a timescale of approximately an hour or lower– indications that indicate the presence of a companion star orbiting tightly around a pulsar.

The group could select the dozen known black widow binaries, confirming the new technique’s accuracy. They then detected a star whose brightness was altered by a factor of 13 every 62 minutes, indicating that it was possibly part of a new black widow binary, which they branded ZTF J1406 +1222.

Looking for the black widow binary

They searched for the star in observances taken by Gaia, a space telescope run by the European Space Agency that keeps exact dimensions of the placement and motion of stars in the sky. Recalling decades-old star measurements from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, the group found that a different far-off star was routing the binary. This third star seemed to orbit the inner binary every 10,000 years, judging from their calculations.

The astronomers have not been able to directly detect gamma or X-ray emissions from the pulsar in the binary, which is typically the method used to confirm the presence of black widows. Therefore, ZTF J1406+1222 is being considered a potential black widow binary, and the team hopes to validate this through future observations.

Burdge explains that the team has observed a star that exhibits a significantly higher temperature on its dayside compared to its night side, and it orbits around an object every 62 minutes. He adds that all indications suggest that it is a black widow binary, but there are some peculiar characteristics that may suggest it could be an entirely new discovery.

The group plans to continue observing the new system and apply the optical strategy to light up more neutron stars and black widows in the sky.

This study was supported partly by the National Science Foundation.

Read the original article on MIT News.

Read more: Do We Exist in a Multiverse?.