Depositphotos

Scientists have produced artificial testicle organoids closely mimicking authentic ones. This advancement offers a hopeful avenue for research, potentially enhancing our comprehension of organ development and leading to treatments for male infertility.

Organoids, miniature 3D organs grown in labs mainly from stem cells, have revolutionized organ modeling, enabling research into diseases and drug testing. In the last ten years, there have been advancements in creating tiny brains, hearts, lungs, stomachs, and colons, with increased complexity and functionality. However, there is currently no organoid available for modeling the testicles.

Cultivating Testis Organoids from Neonatal Mouse Cells

At Bar-Ilan University, Israel, researchers have achieved this by cultivating testis organoids using neonatal mouse cells, which develop structures resembling authentic testes.

Nitzan Gonen, the corresponding author of the study, stated, “Artificial testicles offer a promising platform for fundamental research into testicle development and function, with potential applications in treating sexual development disorders and infertility.”

Disordered testicle development can lead to disorders of sexual development (DSDs), now more commonly known as intersex, encompassing rare conditions involving genes, hormones, and reproductive organs, including genitalia. Malfunctioning development can also contribute to male infertility, where understanding the genetic and environmental mechanisms remains limited.

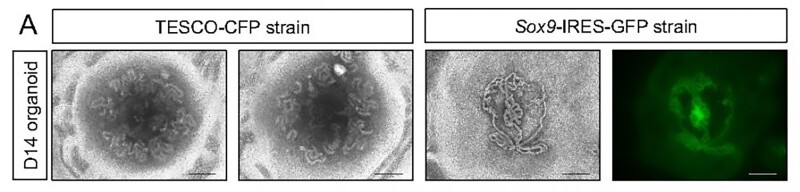

The researchers opted for neonatal mouse testes over embryonic ones, as embryonic testes yield fewer available testicular cells. The mice used in the study were genetically modified to enable tracking of Sertoli cells, crucial for testis formation and spermatogenesis.

Creating Testicular Organoids from Neonatal Mice

Whole testes were extracted from mice aged four to seven days; immature testicular cells were disassembled into single cells and reconstructed in a culture medium containing typical testicular factors. A 3D culture system was employed to facilitate improved formation and maintenance of testicular organoids. By the second day, clear organoids had formed, continuing to grow for nine weeks until collapsing.

The testicles consist of two primary sections: the testis cords, which develop into the seminiferous tubules responsible for sperm production, and the interstitial region, which provides mechanical support for the seminiferous tubules and produces testosterone. Each compartment contains distinct types of cells. By 21 days, the organoids contained all major types of testicular cells, including Sertoli cells, arranged in a manner closely resembling authentic testes. The Sertoli cells formed numerous tubular structures akin to seminiferous tubules.

Stopel et al.

Despite the ease of creating testicular organoids using neonatal cells from newborn mice, researchers experimented with embryonic cells obtained from pregnant females. Their rationale stemmed from the notion that many disorders related to testis development and dysfunction occur during the embryonic stage. Employing the same method, they successfully cultivated testicular organoids from embryonic mouse cells, exhibiting more defined tubular structures than those derived from neonatal cells. However, attempts to utilize adult testicular cells failed to yield organoids.

Signs of Spermatogenesis in Testicular Organoids

Although the testicle organoids did not generate sperm, there were indications suggesting the possibility. Spermatogenesis, a complex process involving sperm stem cells undergoing meiosis to form mature sperm, exhibited low-level expression of meiosis markers in the organoids, particularly between days 21 and 42 of culture, implying the potential presence of small quantities of fully mature sperm at later stages.

Given their striking resemblance to real testes, these organoids offer valuable insights into sex determination mechanisms and hold promise for addressing male infertility.

To conclude, in the future, the researchers aim to develop organoids using human samples. A testicle organoid derived from human cells could aid in the treatment of children with cancer, which often compromises their fertility. The envisioned approach involves harvesting immature sperm cells, freezing them, and subsequently utilizing them to generate a functional sperm-producing organoid.

Read the original article on: New Atlas

Read more: Sandalwood Oil Extract is Effective Against Mouse Prostate Cancer