Astronomers have found two ghostly Goliaths en route to a catastrophic meeting. The newly found pair of supermassive black holes are the closest to colliding ever observed, the astronomers announced on January 9 at an American Astronomical Society meeting in Seattle and in a paper released in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

While close together in cosmological terms at simply 750 light-years apart, the supermassive black holes won’t merge for a few hundred million years. Moreover, the astronomers’ discovery offers a better estimate of how many supermassive black holes are nearing collision in the universe.

That enhanced head count will help researchers in listening for the universe-wide chorus of intense ripples in space-time known as gravitational waves, the largest of which are materials of supermassive black holes near to collision in the aftermath of galaxy mergers. Detecting that gravitational-wave history will enhance estimates of how many galaxies have collided and also merged in the universe’s history.

The distance between black holes

The short distance between the recently found black holes “is fairly close to the limit of what we can spot, which is why this is so exciting,” says research study co-author Chiara Mingarelli, an associate research researcher at the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics in New York City.

Due to the little separation between the black holes, the astronomers could just differentiate between the two objects by combining several observations from 7 telescopes, including NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. (Although supermassive black holes aren’t straight visible through an optical telescope, they are surrounded by brilliant bunches of luminous stars and also warm gas drawn in by their gravitational pull.).

The astronomers discovered the pair rapidly once they began looking, which means that close-together supermassive black holes “are possibly more common than we believe, due to the fact that we discovered these two and we didn’t need to look very far to discover them,” Mingarelli says.

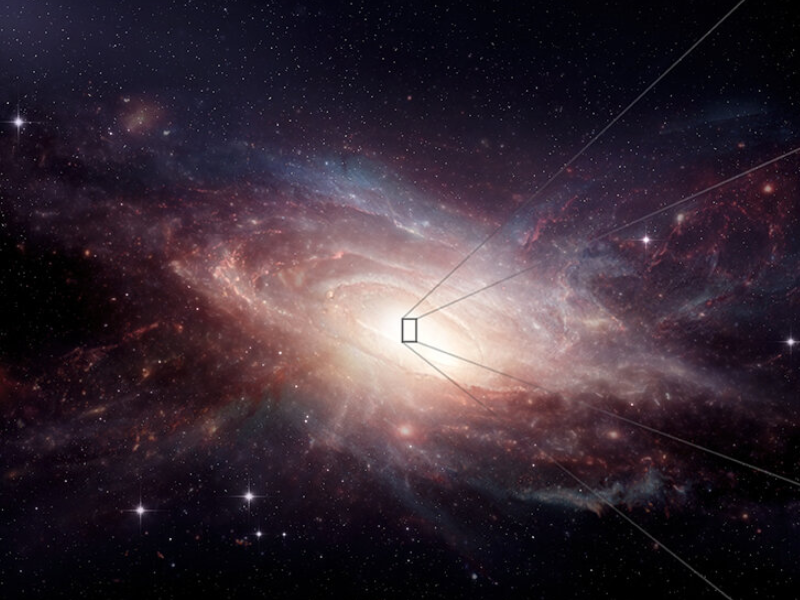

The recently identified supermassive black holes inhabit a mash-up of two galaxies that collided about 480 million light-years away from Earth. Gargantuan black holes live in the heart of most galaxies, growing larger by gobbling up surrounding gas, dust, stars, and even other black holes. Both supermassive black holes identified in this research study are true heavyweights: They clock in at 200 million and 125 million times the mass of our sun.

The black holes

The black holes met as their host galaxies smashed together. Eventually, they will start circling together, with the orbit tightening as gas and also stars pass between both black holes and steal orbital energy. Ultimately the black holes will start generating gravitational waves far stronger than any that have before been spotted before crashing into each other to develop one jumbo-size black hole.

Prior observations of the merging galaxies saw just a single supermassive black hole: Due to the fact that the two objects are so close together, researchers couldn’t definitively tell them apart using a single telescope. The recent survey, led by Michael J. Koss of Eureka Scientific in Oakland, California, combined twelve observations made on 7 telescopes on Earth and in orbit. Although no single observation was sufficient to confirm their existence, the combined information conclusively revealed 2 distinct black holes.

“It is essential that with all these different images, you get the same story– that there are 2 black holes,” says Mingarelli when comparing this new multi-observation research study with previous efforts. “This is where other researches [of close-proximity supermassive black holes] have fallen down in the past. When individuals followed them up, it turned out that there was simply one black hole. [This time, we] have several observations, all in agreement.”.

She and also Flatiron Institute visiting scientist Andrew Casey-Clyde utilized the current observations to estimate the universe’s populace of merging supermassive black holes, finding that it “may be surprisingly high,” Mingarelli states. They forecast that an abundance of supermassive black-hole pairs exists, generating a significant quantity of ultra-strong gravitational waves. All that clamor would result in a loud gravitational-wave history far easier to spot than if the population were smaller. For that reason, the first-ever detection of the background babble of gravitational waves may come “very soon,” Mingarelli says.

Read the original article on PHYS.

Read more: New Study Reveals a Wide Diversity of Galaxies in the Early Universe