Mosquito Bites Successfully Used to Deliver Vaccines

Mosquitoes, notorious for spreading diseases like malaria, have been repurposed by researchers as vaccine carriers. In groundbreaking human trials, these mosquito-borne vaccines showed up to 90% effectiveness, offering a surprising twist on these pests’ role in human health.

Instead of viewing mosquitoes solely as disease vectors, scientists at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine explored their potential as natural vaccine delivery systems. Remarkably, the mosquitoes themselves didn’t need to be genetically modified. The key lay in altering the Plasmodium falciparum parasite, a deadly organism that typically infects humans through mosquito bites.

Public Domain

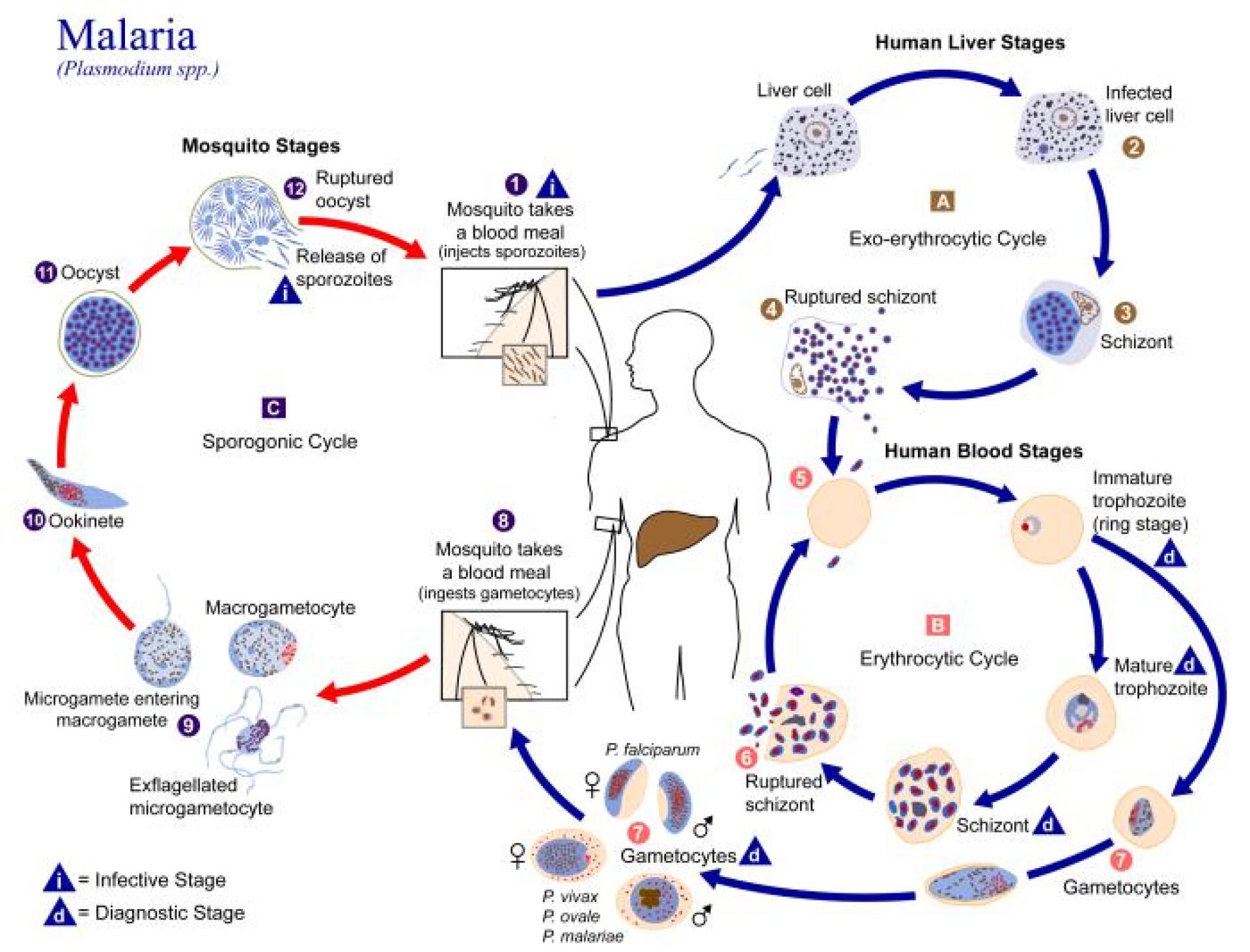

The modified parasites behave like their harmful counterparts until they reach the liver, where they normally multiply and cause malaria symptoms. However, the altered GA2 parasites halt development after six days, releasing antigens instead of secondary parasites. These antigens trigger a strong immune response, effectively training the body to fight off future infections.

Human Trials Show 89% Success Rate for Modified Mosquito-Borne Vaccines

Dr. Graham Beards, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

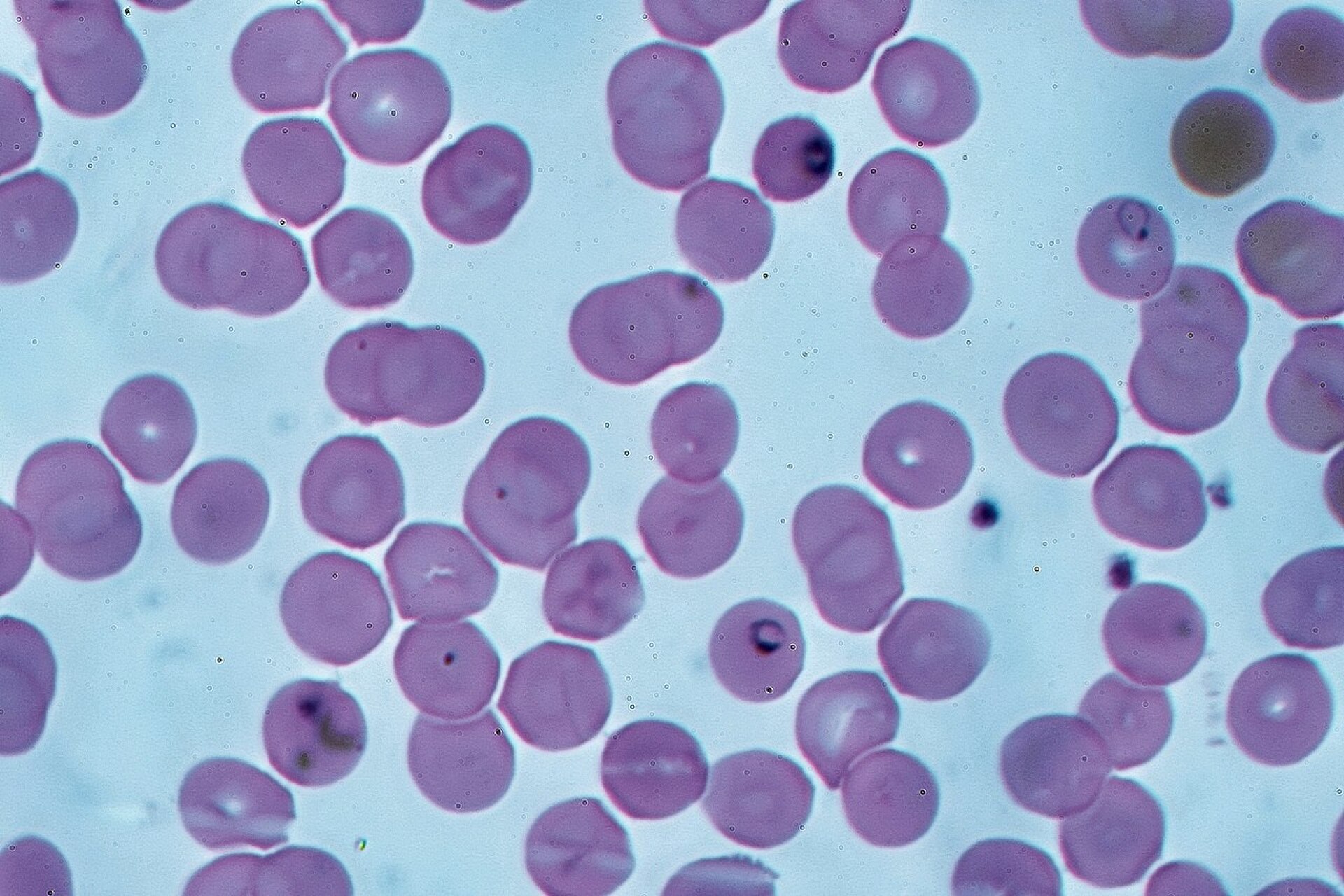

In human trials, volunteers received bites from mosquitoes carrying these altered parasites. Results showed that 89% of participants exposed to GA2 parasites avoided malaria infection when later bitten by mosquitoes carrying unmodified parasites. Side effects were minimal, limited mainly to the itching associated with mosquito bites.

While the concept of mosquitoes delivering vaccines is promising, significant challenges remain. Producing modified parasites and infecting mosquitoes is labor-intensive and expensive, making large-scale deployment difficult. Additionally, this method is specific to malaria and unlikely to work for other diseases.

Despite these hurdles, the study opens up intriguing possibilities for future malaria control and vaccine strategies, with researchers hoping to conduct larger trials to confirm their findings.

Read Original Article: New Atlas

Read More: Scitke