Mystery of the Summer-Killing Volcano Uncovered

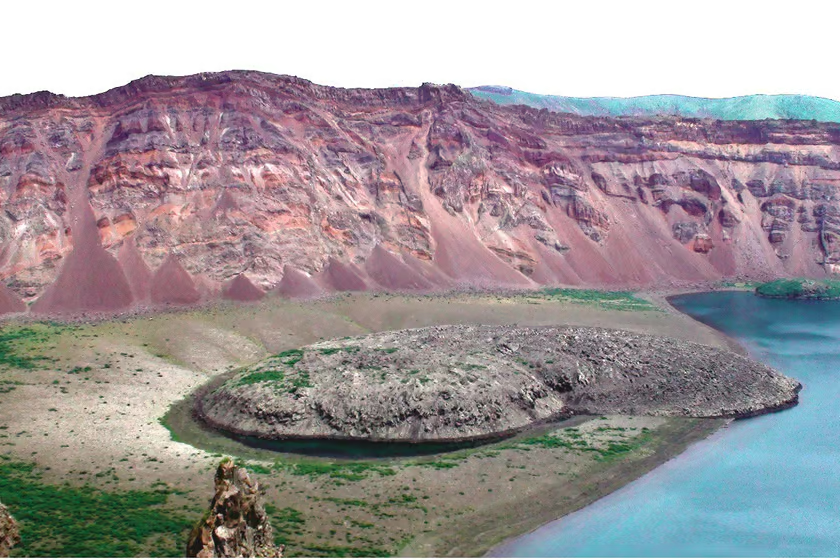

Oleg Dirksen/University of St. Andrews

A longstanding mystery about a year that effectively skipped summer appears to have been resolved. Researchers, using advanced ice core analysis, have determined that the dramatic cooling of 1831 resulted from a massive volcanic eruption in a remote region north of Japan.

1831: A Year of Global Climate Turmoil

In 1831, the global climate took a drastic turn, with temperatures dropping by an average of 1 °C (1.8 °F). The British Isles endured relentless rainfall, making it one of the wettest years of the century, while widespread flooding devastated the countryside. Severe snowstorms struck the Northeastern United States, and failed harvests triggered severe famines in both India and Japan.

Even composer Felix Mendelssohn, while traveling through the Alps, remarked on the bleak weather in his diary: “Desolate weather, it has rained again all night and all morning, it is as cold as in winter, there is already deep snow on the nearest hills…”

A Volcanic Eruption as the Likely Culprit

Although 1831 wasn’t the most infamous “year without a summer,” it was still a harsh anomaly. Over time, scientists came to agree that a volcanic eruption caused the climatic upheaval. The eruption released an estimated 13 million tons of sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere, forming sulfate aerosols. These tiny particles acted like mirrors, reflecting sunlight back into space and significantly cooling the planet.

Oleg Dirksen/University of St. Andrews

The challenge, however, lay in identifying the volcano responsible for the event.

A breakthrough came when a team led by Dr. Will Hutchison from the University of St. Andrews analyzed ice cores dating back to 1831. Using innovative chemical analysis, they matched the microscopic ash particles in the ice—each only a tenth the diameter of a human hair—to a volcanic eruption.

Their findings pointed to the Zavaritskii volcano, located on Simushir, an uninhabited island in the Kuril archipelago. This remote area has a complicated history, having been a point of contention between Russia and Japan and once serving as a secret Soviet submarine base during the Cold War.

“We conducted high-resolution chemical analyses on the ice, which allowed us to pinpoint the eruption to spring-summer 1831,” Hutchison explained. “By isolating and comparing microscopic ash particles, we confirmed the match with samples collected decades ago from the Zavaritskii volcano. The moment we realized the numbers aligned perfectly was a true ‘eureka’ moment.”

Confirming the Eruption’s Timing and Impact

Hutchison and his team delved into historical records to confirm the eruption’s scale and timing, solidifying the connection between the volcanic event and the global climatic impact of 1831.

The study holds relevance beyond its historical significance. Volcanic eruptions capable of disrupting weather patterns, such as Mount Pinatubo’s 1991 eruption in the Philippines, remain a persistent threat. Pinatubo’s eruption lowered global temperatures by half a degree Celsius, underscoring the immense power of natural forces.

This discovery also serves as a reminder of the limitations of geoengineering efforts to control Earth’s climate. The unpredictable influence of large-scale volcanic events could easily undermine even the most well-intentioned human interventions, demonstrating the formidable forces at play in our planet’s systems.

Read the original article on : New Atlas

Read more: Alaska Volcano’s Week-Long Eruption Eases After Massive Ash Cloud Emission