Sauropod’s Last Meal Sheds Light on Eating Habits

Since the late 1800s, sauropod dinosaurs—like Brontosaurus and Brachiosaurus—have been widely accepted as plant-eaters. Yet until recently, no direct evidence, such as fossilized stomach contents, had confirmed this.

A Rare Glimpse Into a Sauropod’s Diet

I was part of a paleontology team working in outback Queensland, Australia, where we discovered “Judy,” an extraordinary sauropod fossil containing the preserved remains of its last meal.

In a new Current Biology paper, we detail these gut contents and report that Judy is not only the most complete sauropod ever found in Australia but also the first with fossilized skin.

Thanks to its exceptional preservation, Judy offers new insight into how these massive creatures fed.

Sauropods’ Reign and Extinction

Sauropod dinosaurs dominated Earth for 130 million years until their extinction 66 million years ago.

Since the 1870s, sauropods have been widely accepted as plant-eaters. It’s difficult to imagine these massive creatures eating anything but vegetation.

Their simple teeth weren’t suited for tearing meat or breaking bones. With small brains and slow movements, they likely lacked the speed or intelligence to hunt prey effectively.

To maintain their enormous size, sauropods would have needed to feed frequently, relying on a consistent and plentiful food source—plants.

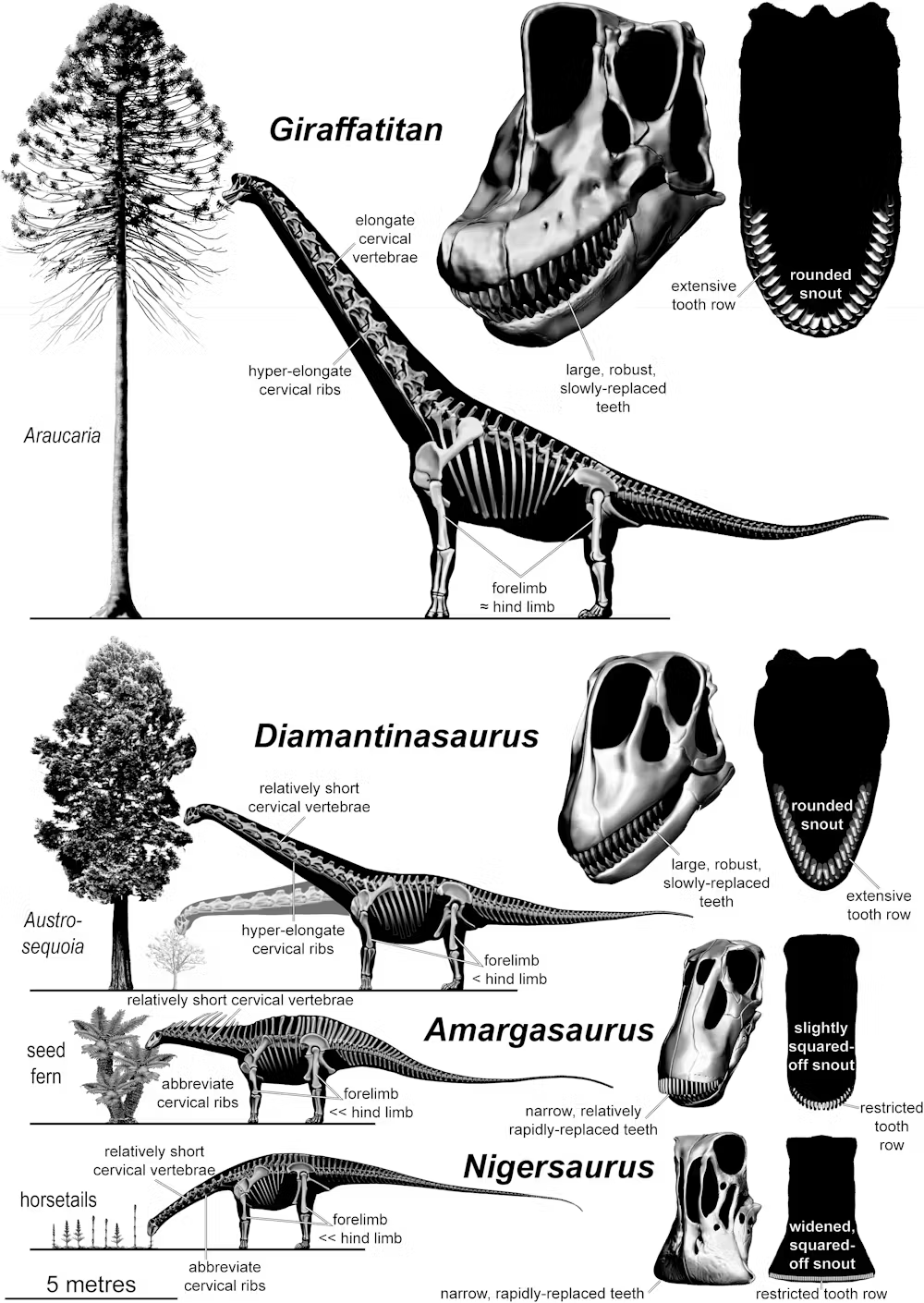

While sauropods shared a generally uniform body structure—large, four-legged, and long-necked—they displayed notable differences upon closer examination.

How Sauropods Differed in Form and Function

Some sauropods had squared snouts with small, fast-replacing teeth limited to the front of the mouth, while others featured rounded snouts and sturdier teeth that extended further back along the jaw. Neck length and flexibility also varied widely—some necks stretched up to 15 meters. Additionally, a few species had shoulders that rose higher than their hips.

Their overall size differed as well—some were noticeably smaller than others. These physical traits would have influenced how high each species could feed and which types of vegetation they could access.

Sauropod discoveries are increasingly common in outback Queensland, largely due to the efforts of the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum in Winton.

In 2017, I assisted the museum in uncovering a sauropod estimated to be around 95 million years old, later nicknamed Judy in honor of the museum’s co-founder, Judy Elliott.

Australia’s Most Complete Sauropod with Preserved Skin and Stomach Contents

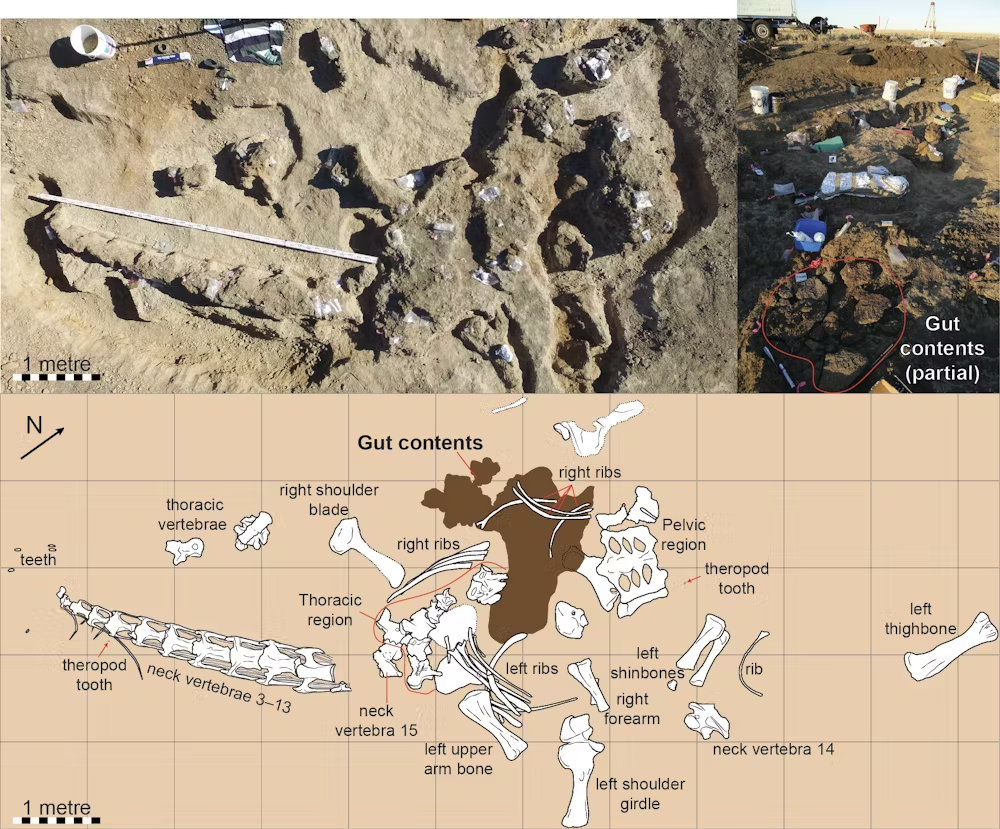

It quickly became clear that this was a remarkable find. Not only is Judy the most complete sauropod skeleton and the first with fossilized skin ever discovered in Australia, but her abdominal area also contained an unusual rock layer—about two square meters in size and averaging ten centimeters thick—densely packed with fossilized plant material.

The presence of this plant-rich layer solely within Judy’s abdominal area, pressed against the inner side of her fossilized skin, led us to ask—had we uncovered the remnants of Judy’s final meal or meals?

If that were the case, we realized we were dealing with something truly unique: the first-ever discovery of sauropod stomach contents.

A Rare Specimen of Diamantinasaurus matildae

By analyzing Judy’s skeleton—carefully extracted from the surrounding rock by museum volunteers—we identified her as Diamantinasaurus matildae.

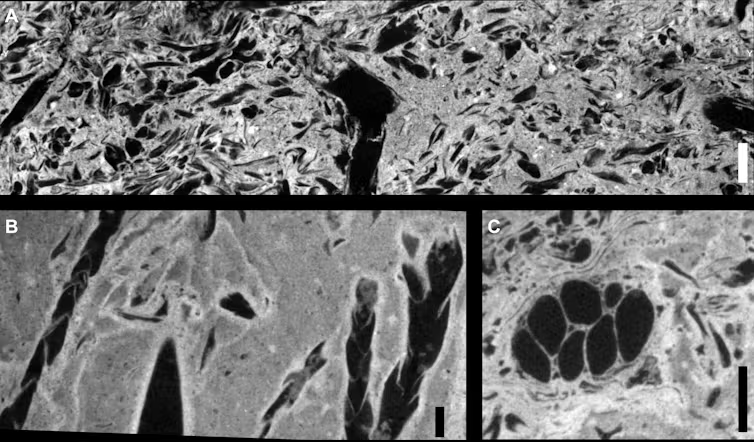

To study her gut contents, we used X-ray scans at the Australian Synchrotron in Melbourne and CSIRO in Perth, as well as neutron imaging at Australia’s Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation in Sydney.

These techniques allowed us to digitally reconstruct the plant material—preserved as voids in the rock—without damaging the fossils.

Analyzing the Composition of Judy’s Final Meal

We carefully removed and analyzed small samples of the gut contents, along with fragments of skin and surrounding rock, to determine their chemical composition.

The results showed that the gut contents had fossilized through microbial activity in an acidic environment—possibly stomach acids—with the minerals likely coming from the breakdown of Judy’s own body tissues.

Judy’s gut contents confirm that sauropods consumed plant material with minimal chewing, relying heavily on gut microbes for digestion.

Crucially, the analysis reveals that just before her death, Judy ate conifer bracts (from relatives of today’s monkey puzzle trees and redwoods), seed pods from now-extinct seed ferns, and leaves from angiosperms, or flowering plants.

At the time, conifers—much like today—would have been tall trees, suggesting Judy fed high off the ground. In contrast, flowering plants during the mid-Cretaceous were mostly low-lying, indicating she grazed at varying heights.

Feeding High

Based on previous finds—particularly teeth—scientists had assumed Diamantinasaurus fed mostly on vegetation high above the ground. The presence of conifer bracts in Judy’s stomach supports this idea.

However, since Judy wasn’t fully grown at the time of her death, the angiosperm remains suggest she also fed closer to the ground. This points to the possibility that some sauropods’ diets shifted slightly as they matured. Still, they remained committed plant-eaters throughout their lives.

Judy’s preserved skin and stomach contents are now on display at the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum in Winton. While I’m not sure how I’d feel about my final meal being on public view after death, I think I’d be okay with it—if it advanced science.

Read the original article on: Science Alert

Read more:Famous ‘Gateway to Hell’ Fire May Be Coming to an End After 50 Years

Leave a Reply