An article released in Environmental Contamination, authored by Saint Louis University (SLU) researchers, demonstrates that human closeness is the best indication of microplastics being located in the Meramec River in Missouri.

Something in the water

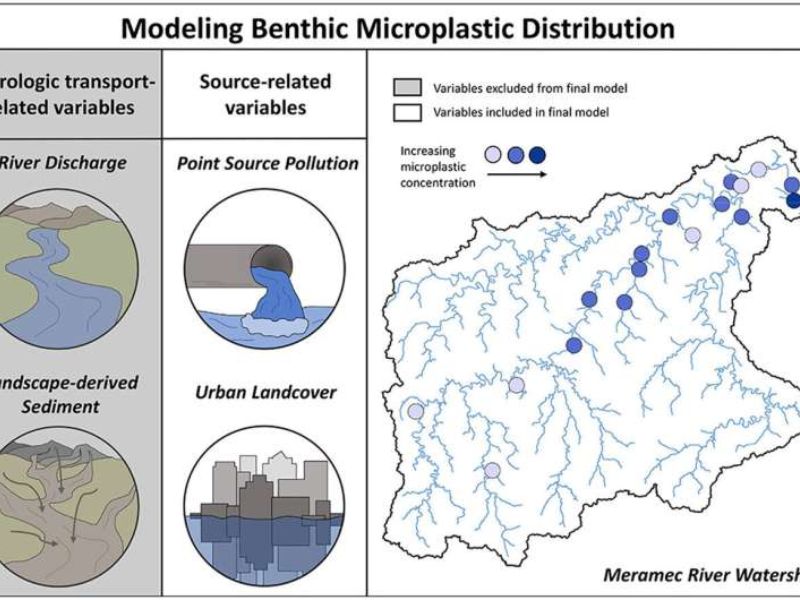

A crew of investigators, carried by Jason Knouft, Ph.D., lecturer of biology, principal researcher with the WATER Institute at SLU, and researcher at the National Great Rivers Investigation and Education Center; and also Elizabeth Hasenmueller, Ph.D., associate lecturer of Earth and atmospheric sciences and associate director of the WATER Institution at SLU, studied degrees of microplastics at nineteen websites along the Meramec River, consisting of places downstream from a significant city along with less populated rural regions.

” What we discovered was that the human being elements fundamentally informed us where the microplastics were,” Hasenmueller stated. “The circulation of microplastics in the basin wasn’t driven by river circulation or sediment inputs. Rather, it was mainly pertaining to how close the website was to inputs of wastewater or a city. Those types of things were the greatest forecasters.”

Microplastics

Microplastics are typically identified as plastic particles tinier than 5.0 millimeters and could be found throughout aquatic, earthbound, and freshwater atmospheres. As a result of the toughness of plastic and the possible dangers of microplastics being discovered in freshwater systems, Knouft, Hasenmueller, and team set out to identify how microplastics get to freshwater systems and what is the best sign to determine where microplastics will be discovered.

To determine where microplastics stayed in a freshwater system and to identify the degrees of microplastics existing, scientists examined the river sediments in the Meramec River watershed. The group also used hydrologic modeling to approximate the significance of river discharge, sediment load, land cover, and wastewater discharge sites to gauge how these elements impact microplastic distribution.

Great discoveries

Throughout their study, Knouft and Hasenmueller made numerous new and yet expected discoveries. The information revealed that the best indication of finding microplastics in the Meramec River was the proximity to human beings. Plastic is produced and taken in by humans; it makes sense that if a river website is near humans, microplastics will be discovered there.

” Before we started, I kept an open mind,” Knouft stated. “I approached it in this form: whatever we find, it will not be surprising to me. If we discovered these points hammer the ecosystem, I would state, ‘Yeah, that makes sense.’ However, if we had found they aren’t really doing anything, I ‘d say, ‘Yeah, that makes sense, due to the fact that they’re these things that are just going through.’”.

Hasenmueller was not amazed that humans were the biggest adding element to finding microplastics in the Meramec River. Still, she was surprised simply exactly how prevalent those microplastics were throughout the basin.

” We knew microplastics would exist, but the quantity of plastic, it was simply everywhere you looked,” Hasenmueller said. “I thought that there could be more of an influence of the stream’s discharge and sediment loads on the circulation than what we saw, which amazed me.”.

What now?

Currently, the attention turns to what could be done to prevent these microplastics from getting to freshwater systems. Individuals can currently take small steps to reduce their plastic usage, such as ensuring plastics go to recycling plants; however, scientists will also be looking ahead to determine large-scale treatments to safeguard our freshwater systems.

” I believe the biggest solution to remedy the problem of microplastics is likewise one of the hardest options, which is reducing the quantity of plastic that we use,” Hasenmueller said. “Almost everything is plastic; our clothing have plastic in them, food and water are saved in plastic, and all of these different points in our everyday life are made of plastic. So having huge companies decrease the quantity of plastic could be impactful due to the fact that there’s just a lot we can do as consumers.”.

SLU students, including co-first writers Teresa Baraza and Natalie Hernandez, added to this research initiative. Various other authors on the paper consist of Chin-Lung Wu, Ph.D., from the biology division at SLU, and Jack Sebok from Washington College in St. Louis.

Read the original article on PHYS.

Read more: COP27: Climate Finance Needs More Transparency

Comments

One response to “Where Human Beings Live, Microplastics End Up In Rivers”